Merry Christmas fellow smart asses! I have no gold, frankincense or myrrh to give, and while I could beat on a drum for you, the ba-rum-pum-pum-pum thing wears thin real quick. Instead, I offer you a review/plot analysis/rant on Avatar, the decade's final blockbuster epic.

When I first heard the film's title some time last summer, I didn't like it. I don't have anything against the word avatar; on the contrary, I think it's a brilliant shred of language. I was put off because James Cameron apparently pilfered it from the excellent animated series by the same name. To my mind, the cartoon was there first, and it's upcoming movie adaptation was better deserving of the title. Besides, seeing how it will be suffering from the directorship of M. Night Shyamalan, it will need all the advertising cache it can get. My opinion of the flick did not improve when I heard about it's universes nomenclature from a friend working on the films advertising. The moon is called Pandora? Really, the most hackneyed mythological reference in science fiction, again? Okay, whatever... but Unobtanium!? Human's are searching for something called un-ob-fucking-tanium? I assume that's supposed to be cute, but it just sounds moronic. There isn't a bus short enough for it to ride on. I understand that you are a visionary Mr. Cameron, but you hired a linguist to help you invent an entire language for the Na'vi, so why not spend five minutes with a writer and see if you can come up with a name that's just a touch sharper?

[Inhale. Exhale. /rant]

Despite my hostilities, Avatar won me over. It is a good movie, and you will most likely have fun if you go see it. You will probably enjoy it even if you don't typically like Sci-fi, because James Cameron is a master of making things that most people like. Even if you found Titanic to be trite and over-long, Avatar is still a spectacle well-worth watching for it's technical brilliance. The movie's ill-named moon has been meticulously rendered, and it's ecology has been populated with flora and fauna that make George Lucas' offerings look like the set pieces for a particularly cheap episode of SG-1. Even Lord of the Ring's Gollum, who exorcised the embarrassing shade of Jar-Jar Binks and proved that CGI characters could be emotionally compelling, seems terribly dated when compared to the Na'vi. There was never a moment in the movie where the illusion fell apart, and I found myself wondering what the mo-cap or voice actors behind the curtain actually looked like. As far as my brain cared, the actors really were big blue cat people. The movie dazzles easily even if you don't spring for the Real3D experience, though the extra $4 or $5 really does make an appreciable difference. For those of you who are wondering where life after HD will take us, this seems a likely path.

There's a story here too, of course, and it is a serviceable scaffold for the brilliant spectacle. It's very easy to figure out who you are supposed to cheer for, and the components of the plot are very familiar. I have heard it compared to Ferngully by a number of people, which surprises me because: (A) I had no idea so many people remember Ferngully and, (B) from a narrative perspective the parallels are almost dead-on. An average joe is magically transported to a naturalistic society where he falls in love with a beautiful woman and together they fight to protect it from evil humans and giant bulldozers. Don't let Avatar's sci-fi trappings fool you. Both films are fairy tales, but what Ferngully accomplishes with pixie dust, Avatar does with an idealized concept of online gaming.

The film's title refers to technology that allows researchers to mentally control biological avatars (created from human and na'vi DNA) to explore Pandora. Humans cannot wander Pandora as they please, you see, because it's very air is poisonous. This establishes a dynamic to similar to online games which are themselves, fantastic worlds that cannot be explored without a surrogate body. The crucial difference, is that Pandora is physically real, as is the Avatar driver's experience of it. Jake Sully, Avatar's aforementioned Average Joe, is a paraplegic ex-marine, and using his Avatar magically gives him back the use of his legs. This is an idealized reversal of a user's typical experience with MMO's, wherein players must give up their physicality to gain the mystical abilities of virtual reality, though the rest of the gaming parallels carry strong. Jake is chosen to learn the ways of the Na'vi; a process that handsomely mirrors leveling up in online gaming. He must learn to speak the local language, hunt the forest's various monsters, and master the Na'vi's magical ability to connect with animals. This last ability bears particular similarity to World of Warcrafts mount system. In fact, a key turning point in the movie entails capturing one's epic flying mount as seen below:

I don't mean to imply that James Cameron intended to make a movie about playing MMOs, but the themes at work certainly cater to the desires of the WoW demographic. In this movie, withdrawing from human society to live in a fantasy world is not only plausible, but noble. Humanity is the bad guy on Pandora, and it's respective avatars are Mr. Corporate Greed and General Texas. Sure, there are good humans, like the nerdy scientists who developed the avatar project to promote cultural exchange and understanding, and Cameron is sure to include one gold-hearted fighter pilot so audiences know he doesn't think all soldiers are bad, but they are all on the Na'vi's side; the right side. Now, I'm no stranger to plots with clear-cut (read: over-simplified) good guys and bad guys where violence is the only solution, but for some reason, it's presence in Avatar bothers me more than usual. As long as the movie is, and it is looong, the climactic battle ending feels too abrupt and easy. I can't help but wonder what would have happened if Cameron stretched the story out over the course of a couple sequels rather than cramming everything into one sitting. I have no doubt that we'll be back to Pandora, though I'm not sure where the franchise will go from here.

Despite those gripes, Avatar is an excellent piece of cinema, and an important victory for big budget film-making in this age of economic dreary. You should give it a watch when you have the chance, because it really is the sort of movie best experienced on the big-screen.

Monday, December 28, 2009

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

Dresden'd for Greatness

About two years ago, I was perusing the Sci-fi/Fantas section in a local bookstore when a description caught my eye; "Think Buffy the Vampire Slayer staring Phillip Marlowe." I may have been aware that the quoted book's title was Small Favor, though I didn't devote much attention to the cover, or who wrote it. The statement crackled with such potential that I snatched up the hardcover, and proceeded to the checkout, only dimly aware of the possibility that I was stumbling into the latest installment of a long running series. If somebody told me I was about to start on Book Ten of the Dresden Files, I may have tried to start at the beginning. A glad thing I didn't know any better. It was one of the best impulse buys of my life. Starting out late didn't hamper my enjoyment of the earlier books in the series, in fact, knowing what was in store made me more charitable toward Jim Butcher during his "warm up period."

The first two books are enjoyable enough, but things really start to pick up here.

The first two books are enjoyable enough, but things really start to pick up here.

If you do not find this even a little bit awesome, The Dresden Files is probably not for you. Also: seek medical attention.

If you do not find this even a little bit awesome, The Dresden Files is probably not for you. Also: seek medical attention.

Despite the fantastic trappings and occasional absurdity of the situations, the action in the Dresden Files is typically driven by very real issues; chiefly, responsibility and relationships. I don't mean the spider-man sort of responsibility about using your powers for good either. There is a bit of that here and there, but usually, the books are concerned with the responsibilities of us mere mortals: sticking to your principals as much as practicality will allow, asking for help despite putting other people out or putting them in danger. These are universals, even if they are broadly drawn, and the fantastic elements of the narrative make them far more interesting and enjoyable than they are in real life.

DOING IT WRONG

DOING IT WRONG

The first two books are enjoyable enough, but things really start to pick up here.

The first two books are enjoyable enough, but things really start to pick up here.Needless to say, the book delivered on the promise of Entertainment Weekly's one liner. The Dresden Files are a helluva lot of fun. The series isn't for everybody; grandma probably won't get it, and fans of "higher literature" including Tolkien devotees will probably look down upon it as low-brow genre fiction. I've even heard people, or at least internet people, refer to it as the Y-chromosomes' answer to Twilight. There is a shred of accuracy to this statement, insofar as the books are clearly written for a male audience, just as Twilight is obviously written for women folk, but the parallels stop there. Unlike Meyer, Butcher can write. The pacing is fast, the plotting starts out serviceable and gets increasingly tighter as the series continues, and the characters, while archetypal, are memorable and believably developed. And most importantly, Butcher doesn't take himself, his protagonist, or his series too seriously. On the contrary, self-deprecation runs high in the Dresden Files. Each book has an element or two which rib's the fantasy genre in one way or another, be by featuring a Billy Goat's Gruff as an antagonist, or a subplot involving a pack of teenage LARPers who gain the ability to turn into were-wolves.

If you do not find this even a little bit awesome, The Dresden Files is probably not for you. Also: seek medical attention.

If you do not find this even a little bit awesome, The Dresden Files is probably not for you. Also: seek medical attention.Despite the fantastic trappings and occasional absurdity of the situations, the action in the Dresden Files is typically driven by very real issues; chiefly, responsibility and relationships. I don't mean the spider-man sort of responsibility about using your powers for good either. There is a bit of that here and there, but usually, the books are concerned with the responsibilities of us mere mortals: sticking to your principals as much as practicality will allow, asking for help despite putting other people out or putting them in danger. These are universals, even if they are broadly drawn, and the fantastic elements of the narrative make them far more interesting and enjoyable than they are in real life.

DOING IT WRONG

DOING IT WRONGNot everything that is Dresden Files is golden however. The Syfy channel (or Sci-fi Channel back at the time of productions) mangles the original series something fierce. Some people liked it well enough, though it tried my tolerance with rather weak writing, and a host of totally unnecessary departures from the source material. Harry Dresden wears a leather jacket as opposed to his signature duster, negating the wild-westish aesthetic of the series. His wizard's staff is now a hockey stick; was this modernization supposed to make him seem hipper some how? Bob, the wisecracking, randy skull that serves as Harry's sidekick is anthropomorphized as a British dandy, and not the good kind like you want. Karen Murphy is now inexplicably a mother. Michael, and the rest of the carpenter family are completely absent. There's really only one way to sum up my feelings about these changes. But like I said, some people really dug it, and it's on Hulu, so you might as well give it a go if you're interested.

The books however, are definitely a must for modern fantasy fans. If you've completed your term at Hogwarts and are wondering where to head next, spending some time in the windy city with Harry Dresden would be a good call.

The books however, are definitely a must for modern fantasy fans. If you've completed your term at Hogwarts and are wondering where to head next, spending some time in the windy city with Harry Dresden would be a good call.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

The Best of All Possible Batmen

You don't need to be The World's Greatest Detective to figure out I'm major Batman fan, but in case my extensive review of The Dark Knight didn't tip you off, I have words to share about Arkham Asylum.

The title of this post might be slightly exaggerated but it gives you a pretty good idea of my opinion about the game. Activision has finally done Bats justice vis-à-vis videogames, halting a dreary, drown-out parade of fail. Their outing (which I experienced via the 360) presents players with the brilliant voice acting of the 90's animated series (which, in my opinion, captures Batman and Joker at their best), the brutal brooding aesthetics of Frank Miller (the only aspect of Miller meriting imitation in my opinion), and the encyclopedic depth of Batman's comic legacy, realized through references, homages, and an impressive character dossier.

Of course, the most important aspect of the game is that it plays like Batman should. The "Freeform Combat" system presents players with the frenetic pacing of the rhythm-action genre in the form of fisticuffs. Conceptually, fights entail frenzied matches of Rock, Paper, Scissors (or Strike, Stun, Dodge) with an emphasis on stringing together long combos to unlock more powerful techniques. It's a much smarter and much more satisfying approach to brawling than typical licensed fair, and even though I happen to be no damn good at it (my combo counter usually peters out at about 8), it's thoroughly enjoyable.

In addition to Zonking and Biffing, (invoked here as old school sound effects; not sexual euphemisms) you also have a utility belt chock full of wonderful toys at your disposal. Batman's signature grapnel gun breaths new life into the hackneyed sneaking trope by allowing you to zip from perch to perch (for some strange reason, the asylum is lousy with indoor gargoyles) to get the drop on fools, as opposed to hiding in boxes or crawling around for five minutes to find the right hiding spot. This is the preferred method for taking out punks with guns, and the only way to navigate situations where thugs have been instructed to kill hostages at the first of Batman. These strategic sequences of cat and mouse, or bat and rats, play more like a strategy or puzzle game than a stealth-action affair, and they truly capture the spirit of Gotham's avenging angel.

My only gameplay gripe, because I've gotta have one, is that the experience feels a little over-engineered at times. You occasionally run into convenient excuses as to why you can't use a gadget, or find yourself forced to clear a room in a very specific way, but I can't stay mad at the game. The very fact that it bothers to explain itself is essentially a good quality, and it's engineering almost always works in the service of variety as opposed to tedium. All the same, I can't help but long for a freer game based on the same model, like an open-ended affair in Gotham.

Lesser oversights include the omission of Shirley Walker's spine-chillingly excellent Batman theme, and the complete absence of Robin. Oracle and Jim Gordan make for good company, but it would have been nice to see at least one of Bruce Wayne's many wards put in an appearence. This is not Christopher Nolan's realistic universe, and therefore there is no excuse to exclude a boy wonder. At the same time, I'm happy to see that the game pays no attention to Batman RIP or Battle for The Cowl. Don't get me wrong, Bruce Wayne has had a hell of a long run, and I can see how killing him off could breathe new life into the Batman mythos, but I'm happy that we got a game that captures him in his prime.

To close on a related tangent, those who are disappointed, or hopelessly confused by the way DC handled the Death of Batman may find some solace in Neil Gaiman's Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?. Then again, you might just be more confused. The story (which is, in typical Gaiman fashion, a collection of stories) stands in 'the gutter' between Batman RIP, Final Crisis, and Battle for Cowl, and offers a brief, metafictional look at Bruce Wayne as Batman that is moving and appropriate, if a little sentimental for modern tastes. It is simultaneously an epitaph for his Era, and an indication of what is to come in terms of comic story-telling.

The title of this post might be slightly exaggerated but it gives you a pretty good idea of my opinion about the game. Activision has finally done Bats justice vis-à-vis videogames, halting a dreary, drown-out parade of fail. Their outing (which I experienced via the 360) presents players with the brilliant voice acting of the 90's animated series (which, in my opinion, captures Batman and Joker at their best), the brutal brooding aesthetics of Frank Miller (the only aspect of Miller meriting imitation in my opinion), and the encyclopedic depth of Batman's comic legacy, realized through references, homages, and an impressive character dossier.

Of course, the most important aspect of the game is that it plays like Batman should. The "Freeform Combat" system presents players with the frenetic pacing of the rhythm-action genre in the form of fisticuffs. Conceptually, fights entail frenzied matches of Rock, Paper, Scissors (or Strike, Stun, Dodge) with an emphasis on stringing together long combos to unlock more powerful techniques. It's a much smarter and much more satisfying approach to brawling than typical licensed fair, and even though I happen to be no damn good at it (my combo counter usually peters out at about 8), it's thoroughly enjoyable.

In addition to Zonking and Biffing, (invoked here as old school sound effects; not sexual euphemisms) you also have a utility belt chock full of wonderful toys at your disposal. Batman's signature grapnel gun breaths new life into the hackneyed sneaking trope by allowing you to zip from perch to perch (for some strange reason, the asylum is lousy with indoor gargoyles) to get the drop on fools, as opposed to hiding in boxes or crawling around for five minutes to find the right hiding spot. This is the preferred method for taking out punks with guns, and the only way to navigate situations where thugs have been instructed to kill hostages at the first of Batman. These strategic sequences of cat and mouse, or bat and rats, play more like a strategy or puzzle game than a stealth-action affair, and they truly capture the spirit of Gotham's avenging angel.

My only gameplay gripe, because I've gotta have one, is that the experience feels a little over-engineered at times. You occasionally run into convenient excuses as to why you can't use a gadget, or find yourself forced to clear a room in a very specific way, but I can't stay mad at the game. The very fact that it bothers to explain itself is essentially a good quality, and it's engineering almost always works in the service of variety as opposed to tedium. All the same, I can't help but long for a freer game based on the same model, like an open-ended affair in Gotham.

Lesser oversights include the omission of Shirley Walker's spine-chillingly excellent Batman theme, and the complete absence of Robin. Oracle and Jim Gordan make for good company, but it would have been nice to see at least one of Bruce Wayne's many wards put in an appearence. This is not Christopher Nolan's realistic universe, and therefore there is no excuse to exclude a boy wonder. At the same time, I'm happy to see that the game pays no attention to Batman RIP or Battle for The Cowl. Don't get me wrong, Bruce Wayne has had a hell of a long run, and I can see how killing him off could breathe new life into the Batman mythos, but I'm happy that we got a game that captures him in his prime.

To close on a related tangent, those who are disappointed, or hopelessly confused by the way DC handled the Death of Batman may find some solace in Neil Gaiman's Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?. Then again, you might just be more confused. The story (which is, in typical Gaiman fashion, a collection of stories) stands in 'the gutter' between Batman RIP, Final Crisis, and Battle for Cowl, and offers a brief, metafictional look at Bruce Wayne as Batman that is moving and appropriate, if a little sentimental for modern tastes. It is simultaneously an epitaph for his Era, and an indication of what is to come in terms of comic story-telling.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Dingos Frisky and Chicken Robotic

It's been quite a stretch since I've talked about animation, what with the abrupt, inexplicable suspension of my Japan's Finest! segment (don't worry, it will be back when you are least prepared for it) and it occurred to me that I never discussed any western animation, which is quite criminal really. Disney and The Simpsons are the obvious points of departure and for that reason, they will be ignored outright. Instead, I would like to discuss [adult swim], a network whose quirky line-up has found particular favor with the internet generations.

I was initially drawn to the network for it's anime, "dubbed down" though it was (quit scoffing you little weaboo brats! we didn't have torrents or crunchyroll.com back then) and I was only dimly aware of the network's original shows. It seems like most people felt the same, because the network really started to gain popularity when it became a refugee camp for prime time toons that more conservative networks had cancelled. Over the years, [as] has continued to develop it's own bizzaire brand of programming, and while most of it is incoherent, mind-scarring, crap, it has produced several gems. Among these, you are probably most familiar with Seth Green and Matthew Senreich's Emmy-winning stop-motion cavalcade...

In many ways, Robot Chicken is the natural evolution of Saturday Night Live. It's a sketch-based show, ripe with amusing nonsense and pop-cultural parodies, but faster paced, cheaper to produce, and funnier (by current comparison anyway) than it's predecessor. Fast and cheap may not necessarily sound like appealing adjectives, but if a sketch bombs in SNL, you get to wait five minutes for the damn thing to play out, while the average chicky robot sketch clocks in at around 30 seconds. You're on to the next joke before you can decide whether you liked the last one or not. I will concede that a certain degree of physical comedy is lost in the transition from actor to action figure, though (sadly) it's less than you might expect. Also, GI Joes typically have less trouble with the booze and drugs. Hey-oh!

It's also clear that Seth Green learned a thing or few from Seth McFarlan while working on Family Guy; specifically, how to play to your demographic with relevant pop-cultural references. Each episode of Robot Chicken balances it's satires of the now (300, Resident Evil, Mario Kart) with parodies of the late 80s and early 90s (Rainbow Bright, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Transformers). Even more importantly, Green and Senreich have a gift for locking on to the embarrassing or absurd aspect of those things you used to love and viciously ridiculing them. The internet generations live in a perpetual state of iteration; we constantly destroy who we are to become somebody new. Perpetually. Indefinitely.

This cynical "anti-nostalgia" was present from the founding of [adult swim] in programs like The Brak Show, Sealab 2021, and Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law, which revive and twist classic cartoons like so many sons wished back to life by a gnarled monkey paw (too obscure? ah what the hell, we'll go with it). These early efforts pale before The Venture Brothers, however.

The show is parody of Johnny Quest and the Hardy Boys. It's a simple premise, one that sounds like it could be very easily exhausted in a single sitting. Indeed, one of the episodes of Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law entails a custody battle between Race Bannon and Dr. Quest for Johnny and Hadji. It was a funny enough episode, but you knew every joke before it happened. Venture Brothers is admittedly starting to show some strain in its 4th season, but it had 3 seasons of solid gold and it's still mostly enjoyable because it simultaneously sustains the absurd dynamics of it's source material while mocking itself with modern cynicism.

The titular brothers, Hank and Dean Venture both behave as if they were still in cartoon's Hanna-Barbera era (lolrhyme). Hank is an impulsive idiot who idolizes batman and Dean is a neurotic simpering milquetoast. Their father, Rusty Venture, a former "boy adventurer" himself, is not only cirminally negligent but borderline evil, yet he is rendered oddly sympathetic through a severe inferiority complex and his general haplessness. Brock Samson, the family's former-secret agent bodyguard, strikes an endearing balance between housewife and homocidal maniac, and the cast is rounded out by a number of delightful supporting characters like Doctor Orpheus, Molotov Cocktease and Henry Killinger.

Perhaps the most innovative twist of the venture universe is the institutional relationship between heroes and villains. The Guild of Calamitous Intent assigns each villain a hero or team to antagonize, or "arch", as an arch nemesis. Both hero and villain must adhere to a convoluted code of conduct in their mutual aggression that lampoons the hackneyed conventions of the good and evil dynamic. The absurdities of the code prevent either party from ever accomplishing anything, allowing the show to capture the mundane spirit of everyday frustrations while remaining true to the laughable formula of action-adventure cartoons. In fact, it's interesting to note that the aforementioned strain evident in the show's most recent season stems from the fact that static characters are finally starting to change. As much as the internet generation loves changing themselves, they tend to abhor change in the familiar.

The final show I'd like to talk about is a personal favorite.

How to describe Frisky Dingo? Well, to begin with, the title has nothing to do with the plot. Like Venture Bros, the absurdity of the good and evil dynamic is central to the show, and it is captured through the unusual relationship between Killface, a verbose hulking super villain trying to raise funds for his doomsday device (see below), and Xander Crews, a millionaire playboy/superhero/impossible douche bag.

To accommodate bankrupt attention-spans like mine, each episode is a bite-sized 15 minutes, but like bonbons, they are best enjoyed when many are consumed in a single sitting. For all it's apparent (and actual) nonsense, there are some impressive narrative circles and a lot of running gags to be enjoyed.

I was initially drawn to the network for it's anime, "dubbed down" though it was (quit scoffing you little weaboo brats! we didn't have torrents or crunchyroll.com back then) and I was only dimly aware of the network's original shows. It seems like most people felt the same, because the network really started to gain popularity when it became a refugee camp for prime time toons that more conservative networks had cancelled. Over the years, [as] has continued to develop it's own bizzaire brand of programming, and while most of it is incoherent, mind-scarring, crap, it has produced several gems. Among these, you are probably most familiar with Seth Green and Matthew Senreich's Emmy-winning stop-motion cavalcade...

In many ways, Robot Chicken is the natural evolution of Saturday Night Live. It's a sketch-based show, ripe with amusing nonsense and pop-cultural parodies, but faster paced, cheaper to produce, and funnier (by current comparison anyway) than it's predecessor. Fast and cheap may not necessarily sound like appealing adjectives, but if a sketch bombs in SNL, you get to wait five minutes for the damn thing to play out, while the average chicky robot sketch clocks in at around 30 seconds. You're on to the next joke before you can decide whether you liked the last one or not. I will concede that a certain degree of physical comedy is lost in the transition from actor to action figure, though (sadly) it's less than you might expect. Also, GI Joes typically have less trouble with the booze and drugs. Hey-oh!

It's also clear that Seth Green learned a thing or few from Seth McFarlan while working on Family Guy; specifically, how to play to your demographic with relevant pop-cultural references. Each episode of Robot Chicken balances it's satires of the now (300, Resident Evil, Mario Kart) with parodies of the late 80s and early 90s (Rainbow Bright, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Transformers). Even more importantly, Green and Senreich have a gift for locking on to the embarrassing or absurd aspect of those things you used to love and viciously ridiculing them. The internet generations live in a perpetual state of iteration; we constantly destroy who we are to become somebody new. Perpetually. Indefinitely.

This cynical "anti-nostalgia" was present from the founding of [adult swim] in programs like The Brak Show, Sealab 2021, and Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law, which revive and twist classic cartoons like so many sons wished back to life by a gnarled monkey paw (too obscure? ah what the hell, we'll go with it). These early efforts pale before The Venture Brothers, however.

The show is parody of Johnny Quest and the Hardy Boys. It's a simple premise, one that sounds like it could be very easily exhausted in a single sitting. Indeed, one of the episodes of Harvey Birdman Attorney at Law entails a custody battle between Race Bannon and Dr. Quest for Johnny and Hadji. It was a funny enough episode, but you knew every joke before it happened. Venture Brothers is admittedly starting to show some strain in its 4th season, but it had 3 seasons of solid gold and it's still mostly enjoyable because it simultaneously sustains the absurd dynamics of it's source material while mocking itself with modern cynicism.

The titular brothers, Hank and Dean Venture both behave as if they were still in cartoon's Hanna-Barbera era (lolrhyme). Hank is an impulsive idiot who idolizes batman and Dean is a neurotic simpering milquetoast. Their father, Rusty Venture, a former "boy adventurer" himself, is not only cirminally negligent but borderline evil, yet he is rendered oddly sympathetic through a severe inferiority complex and his general haplessness. Brock Samson, the family's former-secret agent bodyguard, strikes an endearing balance between housewife and homocidal maniac, and the cast is rounded out by a number of delightful supporting characters like Doctor Orpheus, Molotov Cocktease and Henry Killinger.

Perhaps the most innovative twist of the venture universe is the institutional relationship between heroes and villains. The Guild of Calamitous Intent assigns each villain a hero or team to antagonize, or "arch", as an arch nemesis. Both hero and villain must adhere to a convoluted code of conduct in their mutual aggression that lampoons the hackneyed conventions of the good and evil dynamic. The absurdities of the code prevent either party from ever accomplishing anything, allowing the show to capture the mundane spirit of everyday frustrations while remaining true to the laughable formula of action-adventure cartoons. In fact, it's interesting to note that the aforementioned strain evident in the show's most recent season stems from the fact that static characters are finally starting to change. As much as the internet generation loves changing themselves, they tend to abhor change in the familiar.

The final show I'd like to talk about is a personal favorite.

How to describe Frisky Dingo? Well, to begin with, the title has nothing to do with the plot. Like Venture Bros, the absurdity of the good and evil dynamic is central to the show, and it is captured through the unusual relationship between Killface, a verbose hulking super villain trying to raise funds for his doomsday device (see below), and Xander Crews, a millionaire playboy/superhero/impossible douche bag.

To accommodate bankrupt attention-spans like mine, each episode is a bite-sized 15 minutes, but like bonbons, they are best enjoyed when many are consumed in a single sitting. For all it's apparent (and actual) nonsense, there are some impressive narrative circles and a lot of running gags to be enjoyed.

Friday, October 23, 2009

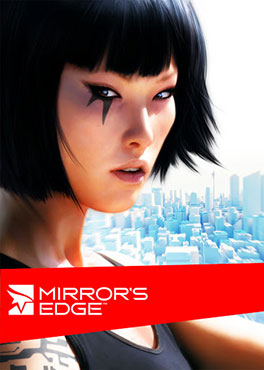

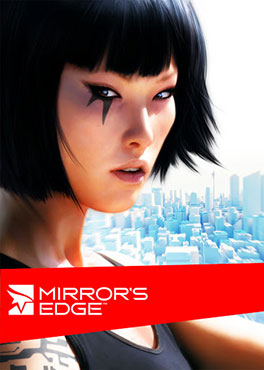

Falling Short of Vertigo

Mirror's Edge was a uniquely frustrating experience for me. I’m well aware the game was out last year and as such, nobody in the video gaming world officially gives a shit about it anymore, but Johnny-come-late posts aren’t exactly a rare occurrence here, so kindly deal, or write an angry email.

As a concept, the game glowed with the sort of innovative potential that makes game-design nerds like myself salivate with potential. You play as a spunky rebel named Faith, subverting an Orwellian police-state by delivering illegal messages to various rebel factions throughout a sprawling city. The gameplay is based around free-running, the purest mix of movement and awesome this side of ballet. The story is penned by Rhianna Pratchett, daughter of the much-loved Terry Pratchett. The art-style was also really fresh; the nameless metropolis is primarily rendered in sterile, spotless white, and detailed with impossibly bold, jump-off-the-screen shades of blue, tangerine, green and yellow. Best of all, the experience would be brought to us by a EA; one of the big boys, meaning (to my idealistic mind) that all of these ideas would be backed by deep pockets, major man power, and an advertising campaign which would not allow the title to go overlooked. If Mirror's Edge did well, it would be a major battle won in favor of risk-taking game design.

A great deal of my disappointment stems from a fundamental misinterpretation of the game's intention. I half-hoped, half-believed, that the gameplay would be based on a relay-race sort of model. When violence inevitably arose, I imagined it would consist of evasion and fluid attacks that leveraged your improvisational mastery of the environment. Now that I write it all out, it seems like I was hoping for a modern, more realistic take in Sonic, but there was more to it than that. I was hoping for a game that could, and would, evoke vertigo in the player. An electronic experience that would make my stomach lurch as I pitched my character off buildings.

Veritgo is a big deal to because it is one of the four major types of play; the one that has seen the least representation in video games. It's not terribly surprising, seeing how video gaming is almost always a sedentary (read: lazy-ass) activity, but if a game could inspire that level of physical exhiliration and disorientation, it would be a major breakthrough. We would be closer to making games that captured the visceral thrill of roller costers, hang-gliding, and bungee jumping; types of play based solely on physiological sensation. Some audiences were affected by Mirror's Edge, but I was not among them. Maybe it played differently on PC, though I suspect that the sort of physical experience I crave is inherently rooted in physical movement, which really isn't such a bad limitation; especially if one considers the physical possibilities that exist for videogames beyond the valley of silly plastic peripherals, though that is a subject for another post altogether.

Anyway, although it is understandable that Mirror's Edge fell short of my lofty vertigo inducing ideal, the game also failed to satisfy a host of more reasonable expectations. At every corner, the game purports to be about "freedom of movement" and "breaking the mold" while simultaneously dictating how I should play it. It told me when I had to fight the badguys, what moves I should use to fight them, and which path I needed to take through the deceptively large levels. In fact, the levels are large enough for you to get lost in them, but since exploration is not on the agenda, getting lost means getting stuck or dying. Through some diabolical paradox, the game manages to be infuriatingly vague despite it's dictatorial model; The "runner vision" system which promised to guide me with red highlighting is later subverted by arbitrarily red interiors, and you also have an insipid talking head barking vague orders like "Get to the mall!" Meanwhile, helicopter gunships and rent-a-cops pepper your ass with lead. Worst of all, once you finally recognize which path the game has charted for you, and which move from your repertoire it wants you to use to get there, you can attempt the prescribed maneuver fifteen times and plummet to your doom, only to inexplicably succeed on the sixteenth try, with no appreciable variation. It's this kind of bullshit that sends me into apoplectic, controller smashing fits of rage. Lewis Black would be proud, but my spouse was not pleased.

In addition to forestalled dreams and out-right frustrations, Mirror's Edge also has lots of good ideas that don't quite fly, like the controls. Instead of an antiquated, "Press X to Jump, Hold Y to Dash" set-up, you get a "One Button Per Body Part" config that is similar to Assassin's Creed. I am a big fan of these contextually sensitive control schemes, but many of the predetermined button choices are terrible. Bumper buttons, the slightly retarded brother of trigger buttons, don't see much use outside of shooting games because they are kind of awkward. Assigning jumping actions to the left bumper, the least used button on the Xbox controller, in a game where you must constantly jump feels, plainly wrong.

At this point, I've waded knee deep into the realm of personal gripes, so I think I'll call it a day. Mirrors Edge has a lot of potential, and it certainly put a lot of interesting ideas about Vertigo in video gaming into my head, but in my book, it misses the mark. It'll be interesting to see what EA will do with the sequel, though I think I'll watch from a safe distance.

As a concept, the game glowed with the sort of innovative potential that makes game-design nerds like myself salivate with potential. You play as a spunky rebel named Faith, subverting an Orwellian police-state by delivering illegal messages to various rebel factions throughout a sprawling city. The gameplay is based around free-running, the purest mix of movement and awesome this side of ballet. The story is penned by Rhianna Pratchett, daughter of the much-loved Terry Pratchett. The art-style was also really fresh; the nameless metropolis is primarily rendered in sterile, spotless white, and detailed with impossibly bold, jump-off-the-screen shades of blue, tangerine, green and yellow. Best of all, the experience would be brought to us by a EA; one of the big boys, meaning (to my idealistic mind) that all of these ideas would be backed by deep pockets, major man power, and an advertising campaign which would not allow the title to go overlooked. If Mirror's Edge did well, it would be a major battle won in favor of risk-taking game design.

A great deal of my disappointment stems from a fundamental misinterpretation of the game's intention. I half-hoped, half-believed, that the gameplay would be based on a relay-race sort of model. When violence inevitably arose, I imagined it would consist of evasion and fluid attacks that leveraged your improvisational mastery of the environment. Now that I write it all out, it seems like I was hoping for a modern, more realistic take in Sonic, but there was more to it than that. I was hoping for a game that could, and would, evoke vertigo in the player. An electronic experience that would make my stomach lurch as I pitched my character off buildings.

Veritgo is a big deal to because it is one of the four major types of play; the one that has seen the least representation in video games. It's not terribly surprising, seeing how video gaming is almost always a sedentary (read: lazy-ass) activity, but if a game could inspire that level of physical exhiliration and disorientation, it would be a major breakthrough. We would be closer to making games that captured the visceral thrill of roller costers, hang-gliding, and bungee jumping; types of play based solely on physiological sensation. Some audiences were affected by Mirror's Edge, but I was not among them. Maybe it played differently on PC, though I suspect that the sort of physical experience I crave is inherently rooted in physical movement, which really isn't such a bad limitation; especially if one considers the physical possibilities that exist for videogames beyond the valley of silly plastic peripherals, though that is a subject for another post altogether.

Anyway, although it is understandable that Mirror's Edge fell short of my lofty vertigo inducing ideal, the game also failed to satisfy a host of more reasonable expectations. At every corner, the game purports to be about "freedom of movement" and "breaking the mold" while simultaneously dictating how I should play it. It told me when I had to fight the badguys, what moves I should use to fight them, and which path I needed to take through the deceptively large levels. In fact, the levels are large enough for you to get lost in them, but since exploration is not on the agenda, getting lost means getting stuck or dying. Through some diabolical paradox, the game manages to be infuriatingly vague despite it's dictatorial model; The "runner vision" system which promised to guide me with red highlighting is later subverted by arbitrarily red interiors, and you also have an insipid talking head barking vague orders like "Get to the mall!" Meanwhile, helicopter gunships and rent-a-cops pepper your ass with lead. Worst of all, once you finally recognize which path the game has charted for you, and which move from your repertoire it wants you to use to get there, you can attempt the prescribed maneuver fifteen times and plummet to your doom, only to inexplicably succeed on the sixteenth try, with no appreciable variation. It's this kind of bullshit that sends me into apoplectic, controller smashing fits of rage. Lewis Black would be proud, but my spouse was not pleased.

In addition to forestalled dreams and out-right frustrations, Mirror's Edge also has lots of good ideas that don't quite fly, like the controls. Instead of an antiquated, "Press X to Jump, Hold Y to Dash" set-up, you get a "One Button Per Body Part" config that is similar to Assassin's Creed. I am a big fan of these contextually sensitive control schemes, but many of the predetermined button choices are terrible. Bumper buttons, the slightly retarded brother of trigger buttons, don't see much use outside of shooting games because they are kind of awkward. Assigning jumping actions to the left bumper, the least used button on the Xbox controller, in a game where you must constantly jump feels, plainly wrong.

At this point, I've waded knee deep into the realm of personal gripes, so I think I'll call it a day. Mirrors Edge has a lot of potential, and it certainly put a lot of interesting ideas about Vertigo in video gaming into my head, but in my book, it misses the mark. It'll be interesting to see what EA will do with the sequel, though I think I'll watch from a safe distance.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

The Cure for The Common Gore Flick

Paranormal Activity is a good horror movie.

It is the best horror movie I've seen since The Ring, and it's scares did not only quench my thirst for terror, but restored my faith in the Horror genre. My faith in general is a rather withered and neglected organ, and the section of it dedicated to horror movies has grown particularly coarse and scarred thanks to Hollywood's recent offerings: uninspired remakes and torture porn. If you like sadistic, visceral scenes of mutilation, you do not only want another movie, you want a different website. Or rather, I want you to go to a different website. Now.

Torture porn fans are grossly unwelcome here because as far as I am concerned, their fetish flicks are the cancer that is killing Horror. Sadistic violence and gore certainly have a place in the genre, but I believe they are best administered in doses that have been carefully measured to provoke as much fear as possible. When violence and gore are taken to excess, we are no longer dealing with Horror, but it's daffy little brother, Camp, which I would argue is a sub-genre in and of itself. Planet Terror and Evil Dead are not Horror films for example, because they do not only invoke humor through horror, but prioritize humor above horror. There may be a few quick scares and gross-out moments, but on the whole the tone is light.

In torture porn, Brutality is the exaggerated element that brings us outside Horror's typical boundaries. The violence can be very innovative (the subgenre's sole virtue), but it is designed to invoke revulsion and disgust rather than fear. There is something of value in fear. It provides a test of ones' mental mettle that makes one aware of the presumptions which support his sense of security and how he copes when said presumptions are challenged. Put simply, it is coming to terms with uncertainty and the unknown. Disgust, by contrast, is the recognition of something that is familiar but unpleasant, and conquering one's sense of disgust simply means putting up with its unpleasantness. The difference between the two processes can be crudely illustrated by exploring a dark cave vs. learning to enjoy the smell of dogshit. I don't like the smell of dogshit, and I'm fine with not liking it. It's dogshit. There is no nutrition or rewarding stimulation to be derived from it, much like Hostel and any SAW title with a roman numeral in it.

Which brings me back to Paranormal Activity, a film at the opposite end of Horror's spectrum. It was made on a budget of nothing, with a cast of nobody, and it still manages to instill curiosity and fear in a delightfuly vicious cycle.

As you may have heard, the film follows a young couple who have recently moved in together, only to be bothered by things- or thing- going bump in the night, and the entire affair is presented as if it were declassified footage of a real-life incident, inevitably begging comparisons to The Blair Witch Project. I trust you good people to parse out the similarities between these two handy-cam horror shows for yourselves, though Paranormal Activity improves on it's predecessor in a number of subtle ways; most notably, it's use of stationary camera work. Almost all of the scary stuff goes down at night while the couple is asleep and we watch them atop a tri-pod in the corner of their bedroom. It may not sound like much, but the immobile perspective shifts our role from mere 'voyeur' to 'prisoner', or even 'victim'. We are not only forced to watch, but forced to watch from a fixed perspective. This sort of immobility creates the perfect climate for claustrophobia to fester and dread to take root in audiences.

Another substantial area of improvement is that the characters are very aware of the camera at all times, and they make you aware of the camera's presence too. In Blair Witch, I frequently found myself wondering, "Why is this being shot?" or "Who is controlling the camera?" and in PA, such queries are never an issue. Most scenes begin with a brief explanation of what we are watching, or about to be watching, and give way to either scares or an interlude between the couple. These interludes run the gamut from mundane and mildly humorous to wrenching shouting matches where we can feel the young lovers' union breaking apart like a limb that is slowly, but insistently being bent against its joint. The initial tension exists within the camera itself, as the young belle is exasperated by her beau's desire to film her at all times. This conflict is the emotional core of the movie, and one gets a clear impression that even if the haunting were to suddenly cease, the young couple would have a few demons yet to face.

And at the expense of a mild spoiler, I will tell you that this is a movie about demons as opposed to a movie about a haunted house. Fortunately, it is a very good movie about demons. In fact I would go so far as to declare Paranormal Activity the natural heir to The Exorcist's dark lineage. You'll have to pardon my purple prose; that film made an impression on me which has yet to fade, despite countless re-watchings and horrendous sequels. The thing that links both movies is not their similar subject matter, or even their sense of claustrophobia, but the way they draw from deep-seated belief to instill fear. There is an impressive legacy of fear surrounding the concept of possession that reflects something primal in human nature. By tapping into that heritage, the superficial details of the haunting gain the rumbling momentum and cold impact of a snowball that has been rolled down a glacier.

Having extolled such high praise, I must confess that I wanted a little more from Paranormal Activity. Ever since the original Exorcist scarred me as a child, I have been waiting for another film to surpass it. This film held such promise, as did The Ring before it, but it did not escalate quite enough to seal the deal. Once again, you will need to excuse my personal fascination, and keep in mind, I have already met people who found PA far more terrifying than The Exorcist. If your looking for a scare this Halloween Season, why not give it a watch and make up your own mind?

It is the best horror movie I've seen since The Ring, and it's scares did not only quench my thirst for terror, but restored my faith in the Horror genre. My faith in general is a rather withered and neglected organ, and the section of it dedicated to horror movies has grown particularly coarse and scarred thanks to Hollywood's recent offerings: uninspired remakes and torture porn. If you like sadistic, visceral scenes of mutilation, you do not only want another movie, you want a different website. Or rather, I want you to go to a different website. Now.

Torture porn fans are grossly unwelcome here because as far as I am concerned, their fetish flicks are the cancer that is killing Horror. Sadistic violence and gore certainly have a place in the genre, but I believe they are best administered in doses that have been carefully measured to provoke as much fear as possible. When violence and gore are taken to excess, we are no longer dealing with Horror, but it's daffy little brother, Camp, which I would argue is a sub-genre in and of itself. Planet Terror and Evil Dead are not Horror films for example, because they do not only invoke humor through horror, but prioritize humor above horror. There may be a few quick scares and gross-out moments, but on the whole the tone is light.

In torture porn, Brutality is the exaggerated element that brings us outside Horror's typical boundaries. The violence can be very innovative (the subgenre's sole virtue), but it is designed to invoke revulsion and disgust rather than fear. There is something of value in fear. It provides a test of ones' mental mettle that makes one aware of the presumptions which support his sense of security and how he copes when said presumptions are challenged. Put simply, it is coming to terms with uncertainty and the unknown. Disgust, by contrast, is the recognition of something that is familiar but unpleasant, and conquering one's sense of disgust simply means putting up with its unpleasantness. The difference between the two processes can be crudely illustrated by exploring a dark cave vs. learning to enjoy the smell of dogshit. I don't like the smell of dogshit, and I'm fine with not liking it. It's dogshit. There is no nutrition or rewarding stimulation to be derived from it, much like Hostel and any SAW title with a roman numeral in it.

Which brings me back to Paranormal Activity, a film at the opposite end of Horror's spectrum. It was made on a budget of nothing, with a cast of nobody, and it still manages to instill curiosity and fear in a delightfuly vicious cycle.

As you may have heard, the film follows a young couple who have recently moved in together, only to be bothered by things- or thing- going bump in the night, and the entire affair is presented as if it were declassified footage of a real-life incident, inevitably begging comparisons to The Blair Witch Project. I trust you good people to parse out the similarities between these two handy-cam horror shows for yourselves, though Paranormal Activity improves on it's predecessor in a number of subtle ways; most notably, it's use of stationary camera work. Almost all of the scary stuff goes down at night while the couple is asleep and we watch them atop a tri-pod in the corner of their bedroom. It may not sound like much, but the immobile perspective shifts our role from mere 'voyeur' to 'prisoner', or even 'victim'. We are not only forced to watch, but forced to watch from a fixed perspective. This sort of immobility creates the perfect climate for claustrophobia to fester and dread to take root in audiences.

Another substantial area of improvement is that the characters are very aware of the camera at all times, and they make you aware of the camera's presence too. In Blair Witch, I frequently found myself wondering, "Why is this being shot?" or "Who is controlling the camera?" and in PA, such queries are never an issue. Most scenes begin with a brief explanation of what we are watching, or about to be watching, and give way to either scares or an interlude between the couple. These interludes run the gamut from mundane and mildly humorous to wrenching shouting matches where we can feel the young lovers' union breaking apart like a limb that is slowly, but insistently being bent against its joint. The initial tension exists within the camera itself, as the young belle is exasperated by her beau's desire to film her at all times. This conflict is the emotional core of the movie, and one gets a clear impression that even if the haunting were to suddenly cease, the young couple would have a few demons yet to face.

And at the expense of a mild spoiler, I will tell you that this is a movie about demons as opposed to a movie about a haunted house. Fortunately, it is a very good movie about demons. In fact I would go so far as to declare Paranormal Activity the natural heir to The Exorcist's dark lineage. You'll have to pardon my purple prose; that film made an impression on me which has yet to fade, despite countless re-watchings and horrendous sequels. The thing that links both movies is not their similar subject matter, or even their sense of claustrophobia, but the way they draw from deep-seated belief to instill fear. There is an impressive legacy of fear surrounding the concept of possession that reflects something primal in human nature. By tapping into that heritage, the superficial details of the haunting gain the rumbling momentum and cold impact of a snowball that has been rolled down a glacier.

Having extolled such high praise, I must confess that I wanted a little more from Paranormal Activity. Ever since the original Exorcist scarred me as a child, I have been waiting for another film to surpass it. This film held such promise, as did The Ring before it, but it did not escalate quite enough to seal the deal. Once again, you will need to excuse my personal fascination, and keep in mind, I have already met people who found PA far more terrifying than The Exorcist. If your looking for a scare this Halloween Season, why not give it a watch and make up your own mind?

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Bound for the Attic?

I fear Joss Whedon will soon be known as "That guy who makes shows that could have been great." Apparently, Fox is pulling Dollhouse from its November lineup in favor of House and Bones re-runs. Even more worrisome is the news that it will be aired in two hour blocks upon its return. For FOX, it is a product that has reached its expiration date, and now they desperately clear their stock before it stinks up the storehouse. Somehow this just doesn't cover it.

To be fair, Dollhouse didn't make things easy on itself. To begin with, the show is inherently hard to market. Describing it's premise is a task which is probably better left to Wikipedia, but essentially, it's about a shady organization (guess what it's called!) that rents out programmable people (Actives or Dolls as you please) to cater to the fantasies of the rich, well-connected and over-privileged. Our heroine, is Echo, a Doll played by Eliza Dushku who has a nasty knack for remembering the fabricated personalities and engagements she's supposed to forget.

The very thing that makes the show so interesting is the thing that makes it so challenging to watch: It strains audiences' abilities to empathize. Whedon's casting and characterization is brilliant as always, but everyone has serious relatability issues. When unprogrammed, the Dolls are amusingly vapid and vulnerable, which is good for a few quick laughs, but quick to wear thin as well. Their programmed presonalities are engaging enough, but too short-lived to get attached. That being said, both Victor and Sierra, the other main dolls aside from Echo, are played brilliantly by Enver Gjokaj and Dichen Lachan, who you probably haven't even heard of before now.

The people who run the Dollhouse are also a real mixed bag. The Dollhouse's resident mind fabricator, Topher, is clever, nerdy and at times disarmingly vulnerable, but he's also obnoxiously conceited and detached from the people whose heads he fucks with for a living . British Boss Lady Adelle is deliciously dry and cold in a curiously endearing way, but she's also the head of an organization that rents people out for everything from sex, to manslaughter, to really dedicated daycare. Head of Security Boyd and disgraced FBI agent Paul Ballard bring some boy scoutly heroics to the mix, but both are administered in controlled doses to prevent them from stealing the show from Echo.

On the subject of Echo; I was skeptical at first as to whether Dushku would be able to carry the show, and while she has given a few trully exceptional performances (like her recent stint as a mother for rent) I'm still a bit ambivilant about her character. Some of her roles seem to bleed together in ways that make it difficult to tell if she is intentionally blending personas (which would be consistent with the shows plot) or if it's just less-than-stellar acting. Furthermore, while Echo's persistent memory affords her a more stable personality than the other dolls, the personality which emerges is that of a perfect doll, or actress. I'm a huge fan of metafiction and the ironies in play here are still a bit much for me to swallow.

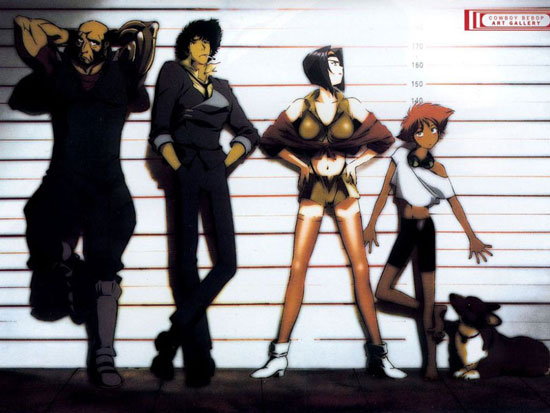

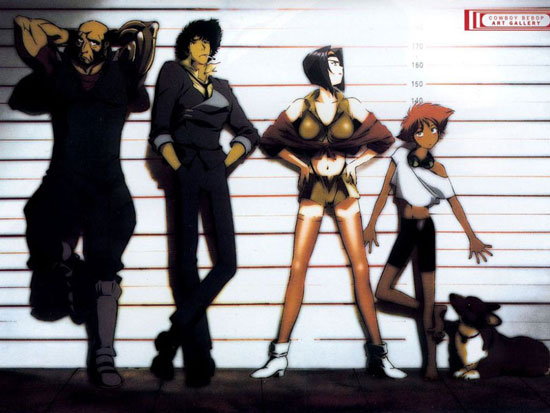

Meet the Dollhouse! From left to right we have Ballard, Victor, Echo, Sierra, Topher, Adelle and Boyd. And yes, every doll is named after a character in the NATO alphabet. So far!

Meet the Dollhouse! From left to right we have Ballard, Victor, Echo, Sierra, Topher, Adelle and Boyd. And yes, every doll is named after a character in the NATO alphabet. So far!

Given all it's inherent challenges, I was fairly certain that Whedon couldn't do anything to sell the show to the kind of viewership FOX was expecting without completely compromising its plot. But then a friend invited me to watch one of the unaired episodes exclusive to the Season 1 DVD, an episode titlted Epitaph One. From what I understand, it was intended to serve as the series de facto ending in case of cancellation, and it does a beautiful job of validating all the characters' grim predictions that the Dollhouse could very easily be the downfall of mankind. Those of you who have not seen the episode but intend to would do well to skip the next three paragraphs, and the general point of this post.

In the episode, we have fastfowarded ten years into the future, and find ourselves faced with a world that has been utterly ravaged by Dollhouse technology. Somehow imprinting signals were unleashed through cellphone signals: everybody who picked up was implanted with a homicidal Doll, and everybody who didn't suddenly found themselves facing off with said doll army. In a way, that scenario is simpler by far than the plot of the first season. You've got a nice, fairly clean binary opposition (the dolls and the people controlling them vs. the survivors), with plenty of opportunity to blur the lines and uncover the mystery of what happened.

If it was up to me to launch my brilliant new show, I'd open with this edgy ruined hell-scape to show people what was at stake, and fill in the blanks as I went along. I'm the sort that sits back and spends a good half hour speculating about stuff with friends and even I was blown away by how fucked up things were, though given the situation presented, the aftermath seemed completely appropriate. As for flashbacking, what better environment could a writer ask for than a world where you can download a person's entire being into a flashdrive?

There are obvious virtues to Whedon's subtler, more gradual approach to the story pf course. We grow increasingly attached to the show's characters as fissures creep through western society, right under our noses. We watch the technology push further and further, breaking boundaries that seem so innocent at the time. If anything, I am a sucker for brilliant plotting. But sadly, most folks aren't patient enough to watch a five year plan unfold. Hell, if Robot Chicken and Family Guy are any evidence, five minutes of continuity is pushing ones' luck. I love both those shows, don't get me wrong, but it saddens me to think that longer term, serialized story-telling is loosing it's place in television.

In conclusion, if you are a Browncoat who was turned off by Dollhouse's early offerings, come back and give it another look, preferably guided by a friend who knows the show well enough to take you through the good stuff. It may already be too late to launch a fan campaign strong enough to save the show, but trying never hurt anything. If you'll excuse me, I'm going to be late for my Treatment.

To be fair, Dollhouse didn't make things easy on itself. To begin with, the show is inherently hard to market. Describing it's premise is a task which is probably better left to Wikipedia, but essentially, it's about a shady organization (guess what it's called!) that rents out programmable people (Actives or Dolls as you please) to cater to the fantasies of the rich, well-connected and over-privileged. Our heroine, is Echo, a Doll played by Eliza Dushku who has a nasty knack for remembering the fabricated personalities and engagements she's supposed to forget.

At it's best, the show is an intelligent exploration of exploitation with some truly fresh sci-fi elements to drive the plot. At it's worse, it's an over-complicated version of The Pretender, at least from a weekly story-telling perspective: The early episodes of the first season saw Dushku trying on outlandish outfits and disposable personas to navigate canned TV perils. Guy who hires Dolls to live out his Most Dangerous Game fantasy? Check. Stuck-up super-star in need of a bodyguard and a lesson on being yourself? Check. Ironically, I think these throw-away scenarios might have been Whedon's attempt at simplifying things for general audiences. Unfortunately, they were still far too confusing for general audiences, and too stilted for his normally stalwart fanbase. By the time the show arrived at truly interesting questions and scenarios ("Can dead people's personalities be imprinted on Actives to get life after death?" "Yes!" "Wow! Altered Carbon much?") almost everybody had lost interest.

The very thing that makes the show so interesting is the thing that makes it so challenging to watch: It strains audiences' abilities to empathize. Whedon's casting and characterization is brilliant as always, but everyone has serious relatability issues. When unprogrammed, the Dolls are amusingly vapid and vulnerable, which is good for a few quick laughs, but quick to wear thin as well. Their programmed presonalities are engaging enough, but too short-lived to get attached. That being said, both Victor and Sierra, the other main dolls aside from Echo, are played brilliantly by Enver Gjokaj and Dichen Lachan, who you probably haven't even heard of before now.

The people who run the Dollhouse are also a real mixed bag. The Dollhouse's resident mind fabricator, Topher, is clever, nerdy and at times disarmingly vulnerable, but he's also obnoxiously conceited and detached from the people whose heads he fucks with for a living . British Boss Lady Adelle is deliciously dry and cold in a curiously endearing way, but she's also the head of an organization that rents people out for everything from sex, to manslaughter, to really dedicated daycare. Head of Security Boyd and disgraced FBI agent Paul Ballard bring some boy scoutly heroics to the mix, but both are administered in controlled doses to prevent them from stealing the show from Echo.

On the subject of Echo; I was skeptical at first as to whether Dushku would be able to carry the show, and while she has given a few trully exceptional performances (like her recent stint as a mother for rent) I'm still a bit ambivilant about her character. Some of her roles seem to bleed together in ways that make it difficult to tell if she is intentionally blending personas (which would be consistent with the shows plot) or if it's just less-than-stellar acting. Furthermore, while Echo's persistent memory affords her a more stable personality than the other dolls, the personality which emerges is that of a perfect doll, or actress. I'm a huge fan of metafiction and the ironies in play here are still a bit much for me to swallow.

Meet the Dollhouse! From left to right we have Ballard, Victor, Echo, Sierra, Topher, Adelle and Boyd. And yes, every doll is named after a character in the NATO alphabet. So far!

Meet the Dollhouse! From left to right we have Ballard, Victor, Echo, Sierra, Topher, Adelle and Boyd. And yes, every doll is named after a character in the NATO alphabet. So far!Given all it's inherent challenges, I was fairly certain that Whedon couldn't do anything to sell the show to the kind of viewership FOX was expecting without completely compromising its plot. But then a friend invited me to watch one of the unaired episodes exclusive to the Season 1 DVD, an episode titlted Epitaph One. From what I understand, it was intended to serve as the series de facto ending in case of cancellation, and it does a beautiful job of validating all the characters' grim predictions that the Dollhouse could very easily be the downfall of mankind. Those of you who have not seen the episode but intend to would do well to skip the next three paragraphs, and the general point of this post.

In the episode, we have fastfowarded ten years into the future, and find ourselves faced with a world that has been utterly ravaged by Dollhouse technology. Somehow imprinting signals were unleashed through cellphone signals: everybody who picked up was implanted with a homicidal Doll, and everybody who didn't suddenly found themselves facing off with said doll army. In a way, that scenario is simpler by far than the plot of the first season. You've got a nice, fairly clean binary opposition (the dolls and the people controlling them vs. the survivors), with plenty of opportunity to blur the lines and uncover the mystery of what happened.

If it was up to me to launch my brilliant new show, I'd open with this edgy ruined hell-scape to show people what was at stake, and fill in the blanks as I went along. I'm the sort that sits back and spends a good half hour speculating about stuff with friends and even I was blown away by how fucked up things were, though given the situation presented, the aftermath seemed completely appropriate. As for flashbacking, what better environment could a writer ask for than a world where you can download a person's entire being into a flashdrive?

There are obvious virtues to Whedon's subtler, more gradual approach to the story pf course. We grow increasingly attached to the show's characters as fissures creep through western society, right under our noses. We watch the technology push further and further, breaking boundaries that seem so innocent at the time. If anything, I am a sucker for brilliant plotting. But sadly, most folks aren't patient enough to watch a five year plan unfold. Hell, if Robot Chicken and Family Guy are any evidence, five minutes of continuity is pushing ones' luck. I love both those shows, don't get me wrong, but it saddens me to think that longer term, serialized story-telling is loosing it's place in television.

In conclusion, if you are a Browncoat who was turned off by Dollhouse's early offerings, come back and give it another look, preferably guided by a friend who knows the show well enough to take you through the good stuff. It may already be too late to launch a fan campaign strong enough to save the show, but trying never hurt anything. If you'll excuse me, I'm going to be late for my Treatment.

Saturday, October 3, 2009

Rule 32

Nerd flicks have been dominating the box office for a couple of years now. The influence of comic books, fantasy trilogies and video games has been rising at a meteoric rate. But on October 2nd, 2009, pop-corn nerd cinema reached a new zenith with Zombieland.

When I first saw the trailer, I remember thinking "this looks pretty awesome, but I probably just saw all the best parts." If you clicked the link, you may find yourself haunted by similar reservations. But fear not; there is a lot more funny to be found in these post apocalyptic wastes. And I am not an easy laugh. Like most people, society has conditioned me to produce a courtesy-laugh with a very low humor threshold for the sake of politeness. Sadly I frequently fall back on it even when I'm watching movies. But this is not real laughter. It is a real-life 'lol' that is more a recognition of attempted humor than a genuine display of mirth. By contrast, this movie has several legitimate ROFL moments. In fact, no fake, truth here to follow: Zombieland is not merely hilarious, but one of the funniest movies I've seen in a long time.

Then again, this movie was designed with people like me in mind, and it was perfectly calibrated to ensure total domination over my demographic. It's clear that Paul Wernick and Rhett Reese have played a lot of video games, and I'm not just talking about zombie blastin' fare like L4D- although the influence of that title is clear, and the film will do the sequel's sales figures a big favor. The influence of Max Brook's Zombie Survival Guide is also apparent, as main character Columbus rattles off a list of zombie surviving maxims simply referred to as "The Rules." Interestingly, these rules are not only narrated, but they pop up on screen whenever applied or applicable, in a comparable manner to the visual motifs of a video games. One gag, (which was sadly surrendered by in one of the trailers), takes this concept even further, referencing a "Zombie Killer of the Week", complete with a flashy, 'achievement unlocked' looking icon.

In case you've been wondering, this post is named after rule 32 for Zombieland which simply advises that one "Enjoy the little things." It's the kind of trite advice which normally pisses me off, because I've always felt there is an urge for compliance and complacency buried beneath the optimism of those truisms. Suggesting one satisfy himself with 'little things' seems to imply that going after big things would be too much trouble. Of course, my suspicions led me to completely disregard the whole "enjoy" part of the equation, so I miss the point entirely. Zombieland helps remind people like me that the difference between living and un-living is enjoying vs. surviving life. I know it sounds pithy, but the gleeful cringe-inducing semi-campy violence involved delivers the movie from preciousness.

From a technical perspective, the movie doesn't break any ground, which is perfectly fine because it doesn't aspire to. The music is mostly familiar, forgettable rock, and the effects are sufficiently bloody. The performances were very enjoyable, though given that every character in the film is a stock character of one kind or another, it was mostly a matter of good casting. That being said, I'm glad that Jesse Eisenberg was chosen to play 'the nerdy sensitive guy' instead of Michael Cerra, and Woody Harrelson makes a hell of a psychotic cowboy. Abigail Breslin of Little Miss Sunshine fame didn't get much in the way of screen time as 'the cute kid' and Emma Stone meets the right balance between wicked hot and playfully bitchy. It's the 'surprise guest' who really steals the show though, but giving him away would be a spoiler punishable by death. As time goes on, the secret will get harder to keep though, so I recommend you get to a theater post-haste. And bring friends. It's that kind of movie.

When I first saw the trailer, I remember thinking "this looks pretty awesome, but I probably just saw all the best parts." If you clicked the link, you may find yourself haunted by similar reservations. But fear not; there is a lot more funny to be found in these post apocalyptic wastes. And I am not an easy laugh. Like most people, society has conditioned me to produce a courtesy-laugh with a very low humor threshold for the sake of politeness. Sadly I frequently fall back on it even when I'm watching movies. But this is not real laughter. It is a real-life 'lol' that is more a recognition of attempted humor than a genuine display of mirth. By contrast, this movie has several legitimate ROFL moments. In fact, no fake, truth here to follow: Zombieland is not merely hilarious, but one of the funniest movies I've seen in a long time.

Then again, this movie was designed with people like me in mind, and it was perfectly calibrated to ensure total domination over my demographic. It's clear that Paul Wernick and Rhett Reese have played a lot of video games, and I'm not just talking about zombie blastin' fare like L4D- although the influence of that title is clear, and the film will do the sequel's sales figures a big favor. The influence of Max Brook's Zombie Survival Guide is also apparent, as main character Columbus rattles off a list of zombie surviving maxims simply referred to as "The Rules." Interestingly, these rules are not only narrated, but they pop up on screen whenever applied or applicable, in a comparable manner to the visual motifs of a video games. One gag, (which was sadly surrendered by in one of the trailers), takes this concept even further, referencing a "Zombie Killer of the Week", complete with a flashy, 'achievement unlocked' looking icon.

In case you've been wondering, this post is named after rule 32 for Zombieland which simply advises that one "Enjoy the little things." It's the kind of trite advice which normally pisses me off, because I've always felt there is an urge for compliance and complacency buried beneath the optimism of those truisms. Suggesting one satisfy himself with 'little things' seems to imply that going after big things would be too much trouble. Of course, my suspicions led me to completely disregard the whole "enjoy" part of the equation, so I miss the point entirely. Zombieland helps remind people like me that the difference between living and un-living is enjoying vs. surviving life. I know it sounds pithy, but the gleeful cringe-inducing semi-campy violence involved delivers the movie from preciousness.

From a technical perspective, the movie doesn't break any ground, which is perfectly fine because it doesn't aspire to. The music is mostly familiar, forgettable rock, and the effects are sufficiently bloody. The performances were very enjoyable, though given that every character in the film is a stock character of one kind or another, it was mostly a matter of good casting. That being said, I'm glad that Jesse Eisenberg was chosen to play 'the nerdy sensitive guy' instead of Michael Cerra, and Woody Harrelson makes a hell of a psychotic cowboy. Abigail Breslin of Little Miss Sunshine fame didn't get much in the way of screen time as 'the cute kid' and Emma Stone meets the right balance between wicked hot and playfully bitchy. It's the 'surprise guest' who really steals the show though, but giving him away would be a spoiler punishable by death. As time goes on, the secret will get harder to keep though, so I recommend you get to a theater post-haste. And bring friends. It's that kind of movie.

Friday, October 2, 2009

They Come in Squalor!

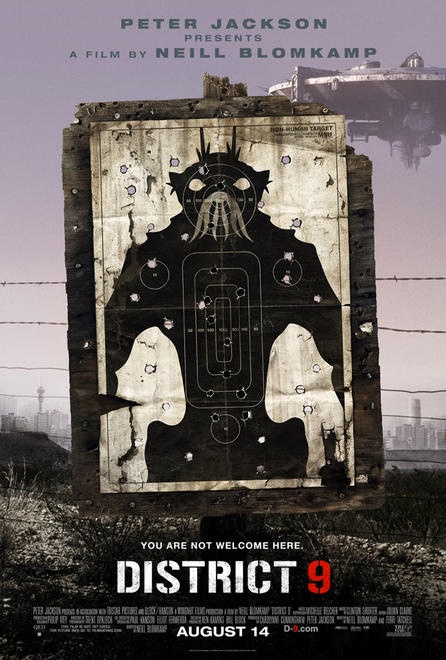

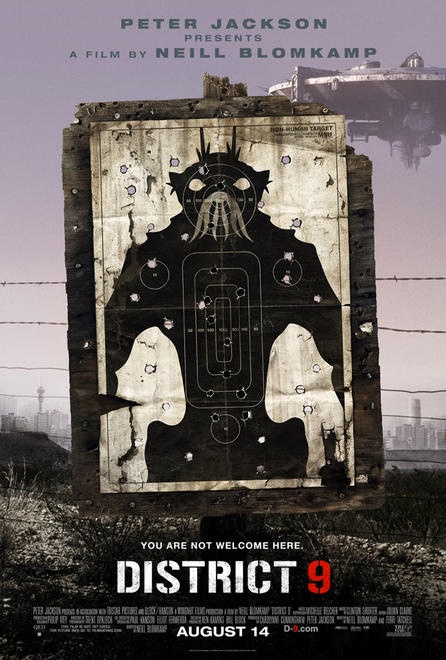

I think enough time has finally passed for me to give District 9 a good talking about without having to worry about catastrophic spoilers. Of course, if you have not seen it yet but you still intend to, do that before reading what I have to say, as the plot will be divulged, and dissected in detail henceforth.

District 9's premise, "what if Aliens came to Earth, not in war or peace, but poverty and desperation?" can be thought of as a return to classic sci-fi form, insofar that it is less concerned with the fantastic trappings of its own genre (laser gunfire, warp drives, paradoxes) , and more concerned with the scenario's social implications. The psuedo-documentary format is a brilliant frame for such examinations, because examining humanity is what documentaries do. We do eventually arrive at flashy firefights, foreign biology and space travel tropes as well, resulting in an intringuing, unique experience. Some critics, whose names I have made a point of not remembering, have complained that the film is simply a mishmash of old and familiar sci-fi tropes, and is therefore not original. Though honestly, if amalgamations cannot be considered original, Homer's a hack, Shakespeare's a schmuck and... you can see where I'm going with this.