I wrote an article for my Introduction to Literary Journalism class titled "My Adventures with Machinima." If you scroll down a couple paragraphs, you can find the third, post-final draft of it, right here on this very web page! As you may surmise from the quoted section of the title, it deals with machinima. Don't know what machinima is? Awesome. Consider it as if it were written just for you, gift-wrapped on a silver platter and garnished with gold-bullion! But first, please indulge me in a bit of

meta-fictional wool-gathering.

I don't really know what to call what I do here, but I now know it isn't Literary Journalism. That is a craft that requires more physicality than I can offer, and a greater ability to relate one reality to a broader communal reality; the finding of universal truths in particular truths. I've learned that I tend to deal better with finding universal truths in fabricated realms, relating non-realities to reality. The story I wanted to tell with this article is one such narrative.

Internet cultures, such as bloggers, gamers and youtube viewers, are shaped by the absence of physical community. While journalists must link physical action to text, the two are already linked for us. Text and action exist on the same plane. They are unified and inextricable. Their intersection is our home. The story I wanted to tell about machinima was one of physical homelessness. Of finding a way to communicate with communities that are only half-there. Of making real movies with virtual objects. A story that demonstrates how physicality and physical journalism falls short in a post-paper communities.

But I had other obligations. I had to demonstrate that I could do 'literary journalism' effectively and report facts along with scenic imagery rooted in physical detail. I had to explain an art-form in its infancy, born from another very new art-form that is still scarcely recognized as such. To my young and inexperienced voice, these agendas tell opposing stories, and the narrative I conceived was lost. Maybe I'll come back to it someday when I can do it justice. Maybe I'll turn to the drink. In the meantime, here it is:

My Adventures with machinima

By Hank Whitson

I sit at my computer, slack-jawed and glassy-eyed as cybernetic soldiers in brightly colored body armor exchange witty dialogue and occasional bursts of gunfire.For the past hour and twenty minutes, I have been watching seasons one and two of Red vs. Blue, a wildly successful machinima series from Rooster Teeth productions made using the Halo series of videogames. I shouldn’t be sitting and staring. I have papers to write and tests to study for, but each episode is only four to five minutes long. Seven at tops. What’s the harm of one more? I click the link to the next episode,

Radar Love, and become viewer number 467,796. I’m lucky my melted brain isn’t dribbling down my chin.

The word machinima, a portmanteau of ‘Machine’ and ‘Cinema,’ is still too young for Merriam-Webster and Oxford English. It can be pronounced “Mah-shin-ee-ma” or “machine-ee-ma,” and like ‘film,’ it can refer to an individual movie or an entire craft of movie-making. The recently established

Academy of machinima Arts and Sciences defines it as “filmmaking within a real-time, 3D virtual environment, often using 3D video-game technologies.” In machinima, the virtual worlds of videogames serve as sets, the game characters are actors, and the graphic models for weapons and objects serve as props. The medium combines aspects of filmmaking, such as cinematography and film editing, with aspects of computer animation and game development, such as 3D model designing and computer programming.

I first heard the term in 2007 when I was playing World of Warcraft (WoW), a popular online game. While I had fun watching the fan-made movies on Youtube, I never paid machinima much attention until I read Alexander Galloway’s book, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, which mentions machinima as a part of an artistic movement referred to as ‘Countergaming.’ According to Galloway, countergaming changes the way people interact with electronic games by modifying or completely repurposing videogame software. I found Galloway’s book last spring as a part of an independent study course examining the relationship between narrative structure and gameplay systems. I was thrilled by his concept of countergaming, not only because I thought it was insightful, but because it was an aspect of gaming—a whole artistic movement no-less—that I was completely unfamiliar with. Given my interest in the relationship between storytelling and play, machinima seemed like the best angle to examine the countergaming movement. I had no idea I was setting out to profile a movement that only half-exists.

Most machinimatographers do not think of themselves as countergamers. Indeed, I have yet to find anymore than a handful of people aside from Galloway who use the term ‘countergaming.’ machinima does repurpose videogame software in a way that radically alters people’s relationship with videogames, however. A machinima-film is completely non-interactive, or at least as non-interactive as television or cinema. Those who watch machinima are no longer relating to the game as players, but as viewers. At the same time, the act of machinima-making forces users to interact with the videogame program from an entirely new perspective. Machinimatographers use the virtual world of the videogame as movie set rather than a platform for play, and as such, they are occasionally required to adjust the parameters of the games’ program. Furthermore, they must use a second computer program to record the footage they create. After the footage has been created, they must use a number of other computer programs such as audio editing software and special effects programs to produce the movie.

From the beginning, machinima has had a sense of humor. Even though machinimatographers typically do not set out to change videogames with their films, as per Galloway’s countergaming movement, machinima have parodied the videogames’ they are based on from the beginning. The consensus among bloggers, online encyclopedias, and machinima makers is that machinima started in 1996 with

“Diary of a Camper.” Diary is a one and a half-minute movie created by a group called The Rangers, using footage from id Software’s Quake, a seminal first-person-shooting (FPS) computer game. The movie portrays a group of soldiers gathered in a virtual cistern. The squads’ leader commands two members of his team to go check out another portion of the level through the in-game text chat, which appears in the upper left corner of the screen. The two soldiers comply, only to be blown away by another soldier who had been laying in wait. Such behavior is generally regarded as poor sportsmanship, and in videogame slang players who practice it are derogatorily referred to as ‘campers.’ After the other members of the squad arrive and avenge their fallen comrade, they comment that the camper seemed familiar. In closing, the commander states that he was John Romero, the father of the FPS genre, and the creator of Quake. From the start, machinima has served as source of humor and commentary on the videogaming community as a whole.

Ironically, the machinima community itself is incredibly fragmented. As an art-form founded in virtual space that films action in virtual space, machinima has no physical forum or home. Machinimatographers do not congregate at cafes, bookstores or theatres, but at web forums, blogs, and Youtube. This online atmosphere is tremendously decentralized and cliquish.

In a lengthy blog post examining the world of machinima circa 2007, Hugh ‘Nomad’ Hancock of machinimafordummies.com writes, “There is no machinima community.” Hancock laments how easy it is for machinima pieces to get lost amongst the sea of video available on the internet. When there are millions of video’s on Youtube alone, carving out an audience for your five minute flick is a daunting prospect indeed. Hancock goes on to explain that machinimatographers have splintered into groups surrounding specific videogames and video-capture programs. This is understandable considering the complexity associated with modern videogame systems. As machinimatographers refine specific filming techniques for a particular game, those techniques tend to become less applicable to other games based on different play-systems.

In the absence of a central forum to inquire about machinima, I decided to try and find machinima-makers on a local level. I learned that UCI offered a class on machinima about four years ago that was taught by associate professor of film and media, Peter Krapp. I had spoken to Krapp earlier in relation to my research on games, and when I asked him for advice about whom to speak to, he referred me to Nathaniel Pope and Ian Beckman, two former graduate-students who had created machinima for his class and continued to work in the field. I wrote emails to Nate and Ian, requesting interviews and inquiring if I might have a chance to watch them work with machinima. Both men agreed to be interviewed, though they mentioned that they live out of town, and stated that they weren’t working on any machinima projects at the present time. Unfortunately, geography and scheduling conflicts prevented me from arranging physical interviews with Nathan and Ian, though the incorporeal nature of our correspondence seemed appropriate for the digitized, decentralized machinima community.

I exchanged a few emails with Nathan Pope before reaching him over the phone. He had a young, enthusiastic voice and began by telling me he was glad to help a fellow Anteater and a friend of Peter’s. I learned that he first got involved with machinima through Prof. Krapp’s class while pursuing a film major, and that he had added minors in Economics and French. He now works with

Xfire, a company specializing in video-capture for videogames. In a gaming context, video-capture specifically refers to digitally recording gameplay footage. Just as filmmaking is only one function of filming, machinima is only one potential use of video-capture. It is an essential tool for bug-testers, and game-designers as well as machinimatographers.

Nate explained the fundamentals of making machinima to me. As with traditional film, the project generally begins with writing a scenario and a rough script. Next, the team will do video-capture, collecting the raw footage that will be edited together to create a movie. It should be noted that footage in machinima does not necessarily conform to behavior that is typical in play. Projects set in first-person shooting games, for example, may not feature any use of guns or weapons. In Rooster-Teeth’s Red vs. Blue series for instance, most footage shows characters speaking to each other. Depending on the type of video-capture program being used, one person may not need to play the part of a camera-man; moving around the other characters and recording their interaction from a first-person perspective. The members of the machinima-making teams who control recorded characters are generally referred to as puppeteers rather actors, since very little in the way of traditional acting is done during this stage of filmmaking.

The next step is the editing process. This entails piecing together the collected video-capture footage, though most of the ‘acting’ that occurs in machinima is also a form of editing. Most machinima narratives are driven by dialogue, which is relayed through voice recordings that are dubbed over the video-captured footage. Nate mentioned that measuring the duration of a scene to correspond to scripted voice acting could be very difficult, and that amateur machinimatographers frequently overshoot or undershoot their scenes; a problem his group ran into while making machinima in class.

One key advantage machinima has over more traditional forms of filmmaking is a very low cost of production. “For a thousand bucks, you’re machinima ready. For ten thousand, you’re professional,” Nate said. The tools you purchase; a powerful computer with top of the line video editing software and a copy of whatever game will serve as your template, can be used to make an entire series of films, whereas traditional films have to hire actors, and build actors for every feature film. Nate also noted that it is much easier to make machinima with small groups of people. He said the average crew for machinima-making is about three to four people.

Nate had a lot to say about the relationship between videogames and machinima: “You can take machinima and appropriate it for whatever you like to do, but it is also an extension of your gaming experience. It extends your experience of play beyond the act of play. It frees the act of gaming for the masses.” As a gamer who has tried and miserably failed to explain complicated videogames to non-gamers on more than one occasion, I can appreciate the value of ‘freeing the act of play.’ Many videogames have some truly fantastic artwork, and the gaming industry has reached a point where it is putting out some truly admirable fiction as well. At times it saddens me to think that some people will never experience that art and those narratives because they are not experienced enough with gaming controls and rules of play. I would never suggest that machinima serve as an absolute substitute for playing videogames as some of their stories can only be appreciated through play, but I believe machinima movies are an excellent form to demonstrate how far videogames have come since Pong.

Getting in touch with Ian Beckman was a bit of challenge, and it’s no surprise why: he’s a busy guy. After trading emails and a failed attempt at talking over MSN, I ended up emailing him my questions, and he responded promptly with links to two other interviews about his work for

Machinima.com, his participation in various film festivals, and his machinima series, Azerothian Super Villains. Ian has worked with a variety of different media, including Flash animation, live-action filming, and according to his

interview at MMOwned.com, he got his start doing stop-motion animation with Legos.

Ian had many insights to share about the production of machinima. When I asked him what goes into making a typical machinima, he responded “Writing is incredibly important because you have only a certain amount of things you are able to do. If you want your characters in Warcraft to mimic The Ghostbusters for example, prepare for a lot of work ahead of you.” Designing situations that accommodate game engines can be a challenge even with an engine as complicated and robust as World of Warcraft. He also expressed his preference for ‘compositing’ machinima, as opposed to directing multiple players over ventrilo—a chat program designed for use in multiplayer games. By using this composite method of machinima-making, Ian doesn’t need to depend on other players to act as his camera men or actors. He noted that players tended to be impatient, and explained: “I save my directing for the voice actors because they’re the ones that really bring life into stiff characters that often repeat animation.”

When I commented that the most popular series in machinima tended to be comedies, Ian responded “I think machinima lends itself to comedies only because you know you’re watching a videogame. It’s just unbelievable, you know?” I do. The current level of graphics and virtual behavior available to film-makers is still extremely limited. Characters in World of Warcraft are capable of laughing, dancing, waving, sobbing, sitting and laying-down animations, but the game’s code currently does not allow for actions that involve other players, aside from combat. It’s incredibly difficult to create dramatic tension when you can’t show your characters hugging each other or shaking hands.

Incredible difficulty isn’t enough to deter a passionate machinimatographer, however. Ian referred me to Martin Falch’s one-and-a-half hour epic,

“Tales of The Past III.” The films’ opening sequence, a full scale war between WoW’s two main factions is definitely dramatic. An armored cavalry thunders across a volcanic wasteland. Green-skinned orcs and trolls cross swords with humans, elves and dwarves. It’s the stuff of Tolkiens’ dreams. Yet when the commanders of each faction address their troops, they use identical arm-waving animations to rally them into battle. There is a poetic irony to be appreciated in this similarity between mortal enemies, but it is only evident to those who are familiar with WoW lore. The movie’s main narrative is even less accessible, as it is based on a specific sword that ties into the game’s lore. The writing didn’t do the film any favors either. I try to watch the film as if I was a first time viewer, who knows nothing about the land of Azeroth or The Scarlet crusade, and I find myself cringing at every close-up. The characters’ faces are expressionless save for a blinking ‘effect’ that looks like it was engineered in Microsoft paint. Throughout the experience, Nathan’s comment about drama and machinima kept echoing in my head: “A lot of machinima is humor-based. It’s easier with comedy. Drama can feel contrived.”

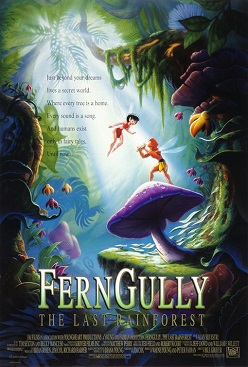

One of the best examples of contrived videogame drama is actually a product of Hollywood. Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, one of the earliest big-budget adaptations of a major videogame property, was universally panned for the limited dramatic range of its nearly photorealistic computer-generated cast. Computer generated imagery (CGI) has come a long way since the release of The Spirits Within back in 2001, however. The tremendous fiscal and critical success of CGI-heavy films like The Lord of the Rings trilogy and Avatar seem to suggest that graphical animation is dramatically viable and tremendously profitable.

It is also interesting to note that Heavy Rain, a title Playstation 3 title marketed as an ‘interactive movie’ as opposed to a typical videogame, was released on February 23rd of this year to great critical acclaim. Other games have earned distinction and created controversy with their liberal use of non-interactive in-game movies or ‘cut-scenes.’ Some players welcome the sequences, feeling that the sequences help tell more complicated and engrossing stories, while others complain that they break up the flow of the action and hinder the gaming experience. Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of The Patriots has been a particularly divisive title for featuring over nine hours of cut-scenes.

This developing trend of cinematic videogames and the enduring presence of CGI in Hollywood may turn people with machinima skills into a wanted commodity for the game and movie industries. In many ways, machinima is the ideal hobby for young filmmakers looking to build a portfolio and gain experience. As Nate and Ian both noted, it is easy and relatively inexpensive compared to traditional filming. It also provides experience with digital technology as well as the major areas of traditional film-design, such as writing, shooting, and editing.

I was curious to know how videogaming companies felt about their games being repurposed to make movies. The videogame industry places great emphasis on intellectual property (IP) cultivation, or developing fictional universes that can act as marketable franchises. Big publishers like Electronic Arts and Activision-Blizzard treat every new game title as a potential franchise-starter, and they defend their copyrights fiercely. If a fan makes an inappropriate video using gameplay featuring an iconic character, like Mario for example, it could potentially mislead and offend would-be buyers. When I contacted Blizzard’s press department by email requesting an interview, they very tactfully explained that they did not have the time to speak to college students doing profiles, and wished me the best of luck with my project.

The last question I asked Ian Beckman was “Do you think playing and knowing about videogames was important for enjoying machinima?” His response surprised me. “Definitely. I know a lot of people who have interest in something like Azerothian Super Villains and still think it has something to do with Warcraft. In my series, I aim to keep the comedy strictly to the characters, so everyone can enjoy them. The name of the game is mass appeal.” I would have thought a machinima master like Ian would be ready to champion his art-form, and proclaim that it was perfectly capable of standing on its own merit. But the truth is most machinima films are about the videogames they are based on. Appreciating their humor requires a familiarity with the terms and context of play. In conclusion, Ian write “It’s unfortunate people haven’t given machinima that much of a chance yet to shine on it’s own accord.”

My adventures with machinima have given me lots of laughs, and I believe that the medium does have a lot of potential. As gaming and online video continue to grow in popularity, I suspect machinima makers will grow in importance and popularity. At the same time, I think there are plenty of machinima that can be enjoyed by a broad audience right now.

To test my theory and help machinima get some exposure, I decide to share one of my favorite movies with my family. My mom and dad gather around the family computer as I pull up Youtube and type in the phrase “Why are we here?” The

first episode of Red vs. Blue pops up third on a long-list of movies. I click on the picture and turn up the volume. The movie opens with a slow pan up the side of a building, revealing two robotic looking soldiers standing side by side on the roof. One soldier is in yellow armor, and the other is in red.

“Hey” the soldier in red asks.

“Yeah?” the yellow soldier responds.

“You ever wonder why we’re here?”

“It’s one of life’s great mysteries isn’t it? Why are we here? I mean, are we the product of some cosmic coincidence, or is there really a god watching everything? You know, with a plan for us and stuff. I dunno man, but it keeps me up at night.”

The camera cuts back and forth between the soldiers without a word, creating the perfect visual representation of an awkward pause. Mom giggles, and Dad is wearing a smirk.

“What?! I meant why are we out here in this canyon?” Red asks

“Oh. Uh…Yeah.” Yellow manages sheepishly.

“What was all that stuff about god?”

“Uh. Hmm… nothing?”

“You want to talk about it?”

“No.”

The exchange is minimalistic. Both soldiers face each-other, with their heads tilting ever-so-slightly in rhythm with the dialogue. Their orange-visored helmets betray no emotion, giving the lines a deadpan delivery. My parents are already laughing loud-enough that some of the dialogue is obscured.

“Seriously though, as far as I can tell it’s just a boxed canyon in the middle of nowhere with no way in or out.” Red says.

“Mm-hmm,” Yellow affirms

“The only reason we have a red base here, is because they have a blue base there. And the only reason they have a blue base over there is because we have a red base here… Even if we were to pull out today, and they were to come take our base? They would have two bases in a box canyon. Whoop-de-fuckin-do.”

The crowd went wild. The remaining two minutes of the episode enjoyed continuous laughter and giggles. You don’t need to be a videogamer to appreciate the absurdity of color-coded aggression. In fact, it’s the sort of non-logic a gamer never notices in the act of play. Asking why you’re shooting at the bad guys or trying to steal their flag from their base would be like asking why one heads to the end-zone in football. Machinima provides a bridge between the world of gaming and the world of narrative. It can fill in the gaps of gaming logic, and address issues in videogaming culture as well. Machinima-making offers dedicated fans a whole new way to experience their favorite titles and the work they produce provides the rest of us with a good laugh.