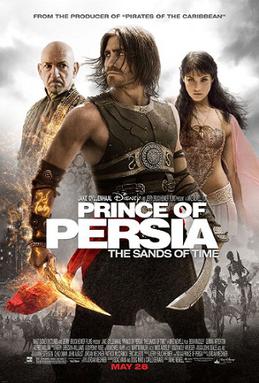

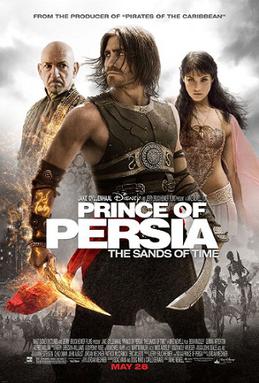

Videogames and Hollywood share an unfortunate history. The 1993 film adaptation of Super Mario Bros, with it’s uncharacteristically dark interpretation of the game’s whimsical Mushroom Kingdom, set a trend of videogame film failures that continues to this day. Mario’s failure was followed by hasty adaptations of the popular fighting game series, Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat. The early aught’s adaptations of the popular Tomb Raider and Resident Evil franchises saw bigger budgets and larger returns, but failed to rise above mediocrity. Hopes and expectations were at an all time high for Hollywood’s most recent videogame venture, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. According to movie-rating aggregation site Rottentomatoes.com, Prince constitutes “…A substantial improvement over most video game adaptations,” even though it holds a meager ranking of 39% positive reviews. With a budget of $200 million and experienced talent such as Jerry Bruckheimer, Jake Gyllenhaal, and Sir Ben Kingsley, one cannot help but wonder where things went wrong.

It must be noted that videogame adaptations of movies suffer from a similar lack in quality. For gamers, it is all but a forgone conclusion that titles released alongside summer blockbusters and holiday season epics will be shovelware: under-developed, derivative software that is designed to capitalize on the film’s hype. By and large, gamers ignore these cheap cash-ins. Sometimes a quality release will be overlooked because it is a licensed property, as was the case with the cult classic, Chronicles of Riddick: Escape From Butcher Bay, the videogame prequel to the 2004 science fiction film

The Chronicles of Riddick. Fittingly enough,

the new Prince of Persia game released alongside the feature film has met with lukewarm reviews.

Gamers have a much harder time ignoring poor film adaptations of their favorite franchises however. This is partially due to the fact that gamers are, amongst other things, extremely passionate fans. After witnessing an atrocious trilogy of videogame adaptations, videogamers created an online petition to try to convince

German filmmaker Uwe Boll to stop making videogame related movies altogether. There is much more than nostalgia at stake when a game is adapted for the silver screen, however. A videogame’s debut on the silver screen is its introduction to the public at large. It opens the experience of that videogame’s fictional universe to people who have never played videogames before. If an adaptation is shallow, bombastic and incoherent, it reflects poorly on that specific title, and the videogame medium as a whole, reinforcing the popular beliefs that games are unsophisticated and juvenile.

But is this portrayal of videogame narratives inaccurate? In her article, “

Why You Will Never Be Happy With Video Game Films,” videogaming journalist Leigh Alexander suggests that the primary problem with videogame movies are videogame narratives. Alexander begins by her discussion with an examination of Resident Evil: Degeneration, a computer animated, direct-to-disc short film based on the popular game franchise. Unlike Paul Anderson’s trilogy of live-action movies based on the popular game series, Degeneration was developed by series’ creators Capcom, and set within the same continuity as the videogames. While Paul Anderson attempted to explain and contextualize the zombie virus that wreaks havoc in the videogame in his films, Degeneration does away with exposition altogether in favor of action. Alexander suggests that fans of the videogames will likely be more receptive to Degeneration, despite its narrative incoherence, because it is truer to their experience of the games than Anderson’s live-action films.

Alexander concedes, “Perhaps to an extent; unfamiliar with the language of games, films often mistranslate a title's appeal.”

This does not appear to be what happened with the movie adaptation of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, however. On the contrary, the film’s creators seem well aware of the fact that they are batting against the odds with their adaptation. Jordan Mechner, creator of the 2003 hit video game on which the movie is based, worked closely with executive producer Jerry Bruckheimer to capture the feel of the game. In an interview with the popular videogame news blog Kotaku, screen writer Doug Miro also professed Bruckheimer’s respect for the source material, and stated, “It still hasn't been proven that a game movie can be done. The perception is that it can't." Miro is hopeful that Prince would turn the tide for videogame movies, just as X-men and Spider-man opened the floodgates to comic-book adaptations.

Being somewhat jaded by previous adaptations, I was pleasantly surprised by the film’s familiarity and respect for its source material. Subtle details such as costuming and set design were immaculately reproduced. There was a great deal of skepticism about the decision to cast Jake Gyllenhaal as the titular prince, but his acrobatic heroics and wry wit accurately captured the spirit of the game’s protagonist. The filmmakers clearly interpreted the game’s charm faithfully and accurately. Yet the movie was not nearly as engaging as the game it was based on. What went wrong?

Alexander’s article presents one possible explanation; “The dominant problem [with videogame films], though, is that the narratives of games are unfortunately not nearly as sophisticated, intelligent, affecting or entertaining as we think they are.” There is no denying the simplicity of the average videogame narratives. Their characters tend to be archetypical, and their plots fall into familiar patterns. But Alexander’s phrasing captures an important detail: Gamers genuinely perceive their experiences in games to be complex, rich narratives.

Jesper Juul examines the unique difficulties of translating narratives between different media in his article “

Games Telling Stories? A Brief Note on Games and Narrative.” To clarify what is being translated, Juul uses Seymour Chatman’s model to divide narrative into Discourse (the telling of the story) and Story. The latter constituent is further divided into Existents (characters, settings, objects) and Events.

Discourse | Story |

Existents | Events |

Narrative |

Juul uses the example of Atari’s 1983 Star Wars arcade game to demonstrate how these narrative building blocks can be rearranged and garbled in the shift from a non-interactive media to an interactive one. The arcade game is solely based on ‘the death star’ sequence of Star Wars: A New Hope, with the player assuming control of a virtual X-wing fighter. There is no Darth Vader or Han Solo. No Tatooine or Millenium Falcon. Any contextual knowledge of the Galatic Empire and the Rebel Alliance is contingent on the arcade cabinet’s art and the player’s knowledge of the film. In addition to excising these crucial existents from the story, the arcade game offers outcomes that directly betray the events of the movie; the player can fail to blow up the Death Star, loosing the game. If the player succeeds in destroying the Death Star, a second one will appear, also betraying the events of the first movie, (though it is amusing to note that the threat of the death star is revived in Return of the Jedi). Clearly, the components of story are subject to warping and fragmentation in the transition from movie to games.

It must be said that Juul’s example is something of a strawman; videogame technology has come a long way since Atari arcade machines, and modern examples of the form are much more capable of telling complicated narratives. Eidos’ and LucasArt’s Lego Star Wars series follows the events of the films quite faithfully (albeit through the filter of Legos). Juul does acknowledge the emergence of “cut-scenes” in games, non-interactive sequences where the player must watch instead of play, but he over-emphasizes their relationship to Existents and Events. I would argue that this mixed presentation is a discursive decision. Alternating between “non-interactive” narration and the capacity for play creates a very complicated relationship between audience and “text.”

Jull acknowledges that his model fails to account for the avant-garde. Movie-watching can be an interactive, discursive experience. Scenes may be interpreted in a variety ways and craft may be analyzed and appreciated on many levels. I would even argue that choosing to simply “receive” the given visual narrative at face value, constitutes a meaningful interpretative decision. Obviously, in videogames the prevalence of interactivity is much more pronounced. The vast majority of ‘the narrative’ will not progress unless you play, (unlike film) and this strongly influences players’ relationships with the game and its characters. Even though the game’s frame narrative is fictitious, the player’s interactions with the game’s rules; his losses and his victories; are real.

I believe this complicated interaction accounts for player’s deep narrative investment in games. Repeatedly experiencing, and eventually overcoming failure over the course of a narrative makes the quest unpredictable and exciting. It creates a second order narratological system, not unlike the second order semiological system Roland Barthes’ uses to describe the mythological. Each isolated victory and defeat in play, carried out in accordance with the game’s ‘text;’ the language established by it’s rules, graphics, and control interfaces can be likened to a single completed story. The sum total of these stories creates the gamers experience with the game as a whole. As with Barthes’ model, I present the following spacialization is only a metaphor:

Discourse (game text) | Story (game text) |

Discourse (game play) | Story (Game play) |

Existents | Events | Existents | Events |

(game play) Narrative |

Narrative (game text) |

When a gametext is transferred to a movie, writers not only need to flesh out the simplistic, conventional characters that currently define the videogame genre; they must also create a more structured, faster paced experience. My greatest complaint concerning the Prince of Persia film is that the fabled Dagger of Time; a weapon with the power to rewind time; sees very little use in the actual movie. In the videogame, players must use the daggers rewinding mechanic frequently to undo botched jumps and fights. It was a revolutionary mechanic for videogames, because it situated a players’ ability to come back from the dead within the narrative context of the game. Contrary to Juul’s assertion that “Game’s are almost always chronological,” I would argue that the stories of videogames are inherently circular. To experience them is to replay them, time and again, exploring their various permutations. Movies are experienced in a single narrative line, regardless of whether the chronology of their plot is shuffled or not.

I suspect that videogame movies will become more successful when their uni-directional narratives start to leverage the circular discourse of gameplay. It is interesting to note that these types of gamic trends are already surfacing in non-videogame movies. Ruben Fleischer’s

Zombieland features a number of these visual motifs that evoke a videogame feel, including richly stylized violence and a number of “rules” for survival that are represented by colorful icons, reminiscent of “achievement” graphics. One scene even depicts a “zombie killer of the week,” a wink at online scoreboards for multiplayer games. More recently, these trends were evident in

Kick-Ass, which featured elaborately choreographed violence, an intense first-person shooting sequence, and a murderous child-hero.

The trailer of the upcoming Scott Pilgrim vs. The World is rife with videogame graphics and sound effects. As a gamer, it is gratifying to see these motifs and patterns migrate to the mainstream, and I look forward to the day that Hollywood does a videogame adaptation justice.