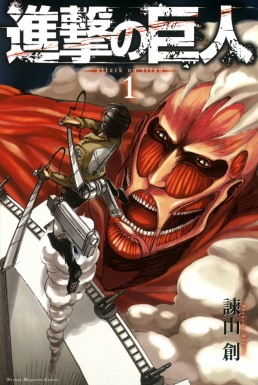

People have accused Isayama's art of being rough and sloppy, but I think it pairs well

with the aesthetics of the world, which alternate between smart, eerie, and bloody.

The show chronicles a steampunk dystopian future where the whole of human civilization exists behind three colossal walls. The walls are the only barriers between us and an endless horde of enormous, oddly-proportioned, and thoroughly androgynous giants that compulsively devour people. Instead of inventing battle mechs as-per-usual, humans fight these colossal menaces by using twin, hip-mounted grappling hooks and gas-propulsion canisters, paired with swords resembling giant exacto-knives. For reasons unknown, the only way to kill a titan is to completely cut through the nape of its neck. It near-instantaneously recovers from everything else, rendering conventional artillery fire useless, and we either lost all of our more advanced technology, or never invented it in the first place. At first blush, it greatly resembles medieval Evangelion, but with a ridiculous body count and considerably less existential whining.

But none of that is what makes Titan awesome. I have long imagined a manga that would take the whole shonen genre to task for its hackneyed tropes. In Titan, willpower and diligence are not enough to overcome the enemy in battle. In Titan, "believing in your comrades" is not only a fallible battle strategy, but a decision that can yield truly tragic results. In Titan, you can even see the beginning of anti-conformist narratives in shonen comics. This is a refreshing change of pace to be sure, but it also has huge cultural implications.

I realize this sounds highly suspect coming from a hyper-normative American. The only compelling cultural heritage I could lay claim to in my adolescence were narratives of anti-conformity and rebellion, and when you hold a hammer, the whole world looks like a box of self-same nails. But I am not arguing here, that Japan has never had anti-conformity stories before (Battle Royale says "Hi" for one). Rather, it is a country with a great deal more to say on the subject--and it has insights that will benefit the entire rest of the world. The job market may be rough here in the US, but the future facing Japanese millenials is positively despondent. Anything less than unflinching academic excellence yields a very bleak future, and this explains why so many comics and shows have deified diligence, and promise readers that working hard and finding friends is a sure pathway to success. In these stories, the hero's awesome power must always be reserved to protect beloved friends from evil, and never to create a legacy for oneself, lest he become taken by the vile current of imperialism.

In Titan it readily becomes apparent that merely defending your borders and toeing the line in society is a recipe for disaster. Humanity has become rotted by corruption behind its walls, where the best and brightest soldiers are recruited to languish in the most corrupt branch of service, and the masses are manipulated by a deceitful religion that worships the walls while selfishly concealing truly damning secrets about the titan threat. The heroes of the story are the survey corps. who strive to reclaim the world that has been taken by the titans. Unsurprisingly, the series creator, Hajime Isayama, has been accused of attempting to rekindle the militant spirit of imperial Japan.

I have a different theory. The Titans do not represent foreigners, but the goliaths in our midst. The corporations and institutions that have proven too big to fail. The survey corps. is not looking to take land away from other humans, but rather, the land that is rightfully human, which has been claimed as grazing grounds for irrational, mindless monsters. As haughty as it sounds to suggest it, Attack on Titan is not about the imperial versus the foreign, but a younger generation overcoming an older one.

Minor anime spoilers are present in this paragraph. Early on in the series, it is revealed that Eren Jaeger, our fated hero, has the power to turn into a titan himself, and as the series continues, we discover that he is not unique. While most titans are mindless, humans with the ability to become titans are shrewd, and rational, with all the power that comes with fifteen meters of height and muscle. These "titan-shifters" represent people who can affect the status quo and this metaphor only gets more explicit as the manga progresses. Even mankind's most capable warriors, such as Eren's superior officer, Levi, and his adopted-sister, Mikasa, can only take down weaker titans, so it is up to people with Titan Powers, to reclaim the world for humans. And if the conspiratorial self-serving status quo remains in power, society, robbed of its ability to grow, will continue to rot until it collapses. End spoilers.

As I watch, I am continually reminded not of other anime, but of George RR Martin's Game of Thrones. A large part of this correlation undoubtedly stems from both creators' willingness, or rather, their apparent gleeful eagerness, to savagely kill off likable characters. But another reason the two shows are so compelling is that they casually break the longstanding rules associated with their genre. Even if you don't give a damn about Isayama's theoretical politics, the show is a delight to watch because you never know for sure what will happen next. Consequently, I cannot recommend Titan highly enough.